Symbols such as the swastika have a long history. To avoid misunderstanding and misuse, individuals should consider the context and past use of Nazi symbols and symbols in general.

–United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

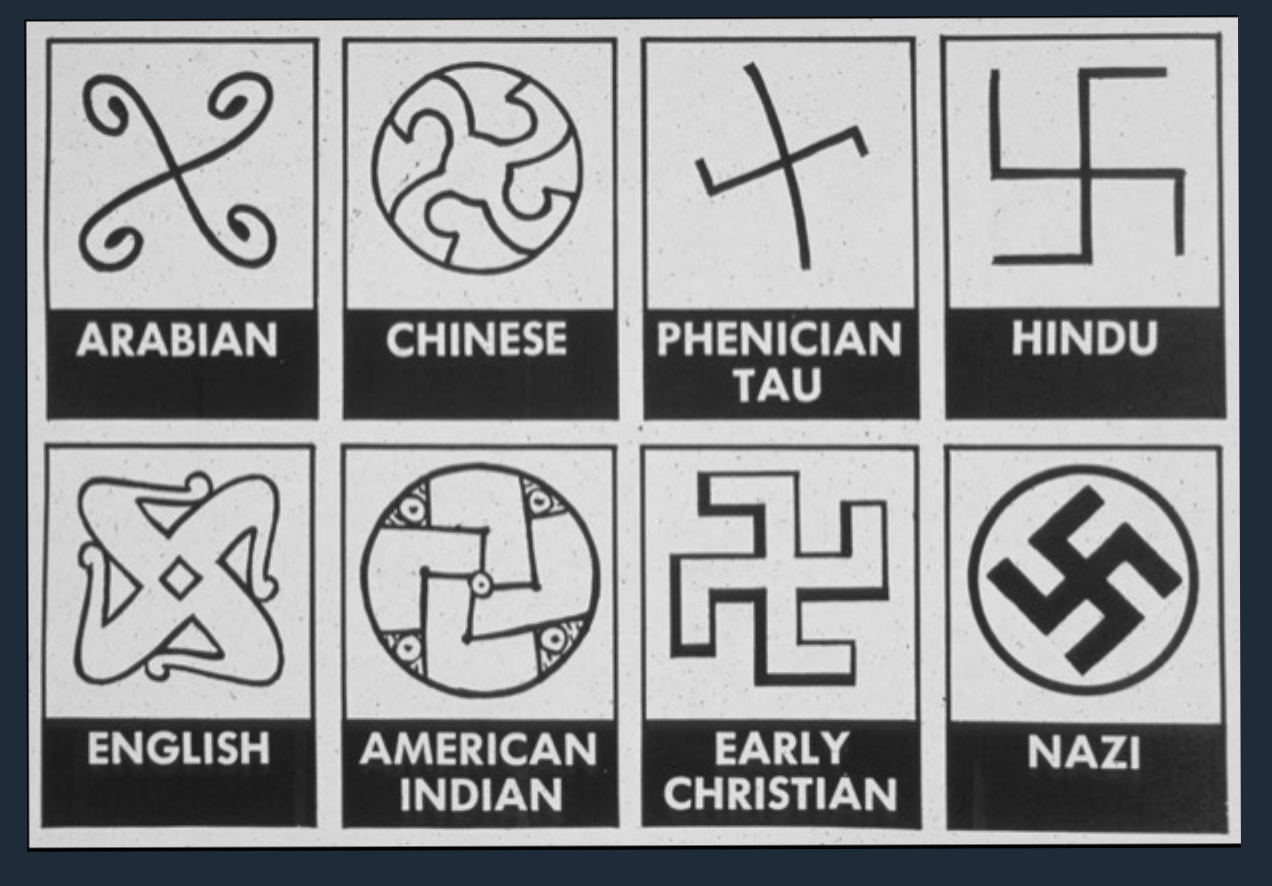

As defined in the Oxford English Dictionary, a swastika is “a symbol in the form of a cross with arms of equal length, each arm bending at a right angle in the same direction (either clockwise or anticlockwise).” For thousands of years, swastikas have circulated within and across communities as a symbol of benevolence and good will. As articulated by Pro-Swastika (n.d.), “The word swastika comes from the Sanskrit svastika. Su meaning well, asti meaning ‘to be,’ and ka as a suffix. The swastika literally means ‘to be well.’” As such, much research has explored how the swastika has circulated as a sacred symbol in many religions and communities across the world (Wilson 1896 (2014); Campion 2014; Munson 2016; Nakagaki 2018).

Despite this benevolent function, in the context of the United States and much of Europe, the swastika is most often recognized as a harmful sign due to its participation in hateful, antisemitic, and white supremacist actions in modern contexts. As is well documented, the swastika has circulated as a symbol of the Aryan race historically in Europe; as an emblem of and propaganda vehicle for the Nazi party in Germany; and as a branding device for Neo-Nazis and contemporary Aryan-identifying Americans (Simi and Futrell, 2015). In addition, as the Swastika Counter Project findings make evident, the swastika circulates today as a white nationalist appeal, a xenophobic marker of Otherness, and a technology of violence (Aronis and Aoki, 2024) that especially targets Jewish people but also other minoritized individuals and communities. The swastika is not banned in the United States like it is currently banned in Germany, Austria, and Poland due to its involvement in and longstanding association with the genocide of six million Jews during World War II, i.e. the Holocaust. Nonetheless, both here and abroad, the swastika is considered by many to be not only offensive but also traumatizing and terrorizing. In fact, Carolin Aronis and Eric Aoki (2024) argue that “Since 1945, [the swastika] has been perceived as the most significant and notorious of hate symbols, representing antisemitism, Jew-hatred, and white supremacy for most of the world, as well as representing Hitler himself, genocide, imperialist warfare, torture, and terror” (5).

Important to note is that despite this infamy, some have recently advocated for a more careful distinction between benevolent and malignant forms and functions of the swastika. A lot of recent research, for instance, has argued that the sign that most Euro-Americans recognize as the swastika appropriated by Hitler’s party is not actually the swastika of Hindu origin but a Hakenkruez (hooked cross).[1] As such, T. K. Nakagaki, Stephen Heller, and others argue that we need to remedy this conflation, educating all people that “the Hakenkreuz is used to instill fear in people while the Swastika is always used for sacred and peaceful purposes” (Heller, n.p.).

The Swastika Counter Project would not disagree with the need for more careful consideration of such perspectives, and as such, we advocate for more public education about the rhetorical history of the swastika. However, our research demonstrates that in the context of the contemporary United States, the swastika does most often function and is most often perceived as a terrorizing tool (or technology) that participates in antisemitism, white supremacy, and white nationalist ideologies and behaviors. In addition, our research findings demonstrate that of the ~1300 swastikas we documented in the United States between 2016 and 2021, higher education institutions and K-12 schools were the most frequently targeted locations. Therefore, we especially advocate for teachers at all levels of education to help deepen students’ understanding of the contemporary and ongoing harms that swastikas perpetuate.

Toward all these efforts, we offer the following bibliography. See also our Lesson Plan page.

[1] According to this research, Hitler never used the word “swastika” to identify the sign appropriated for his party. Instead, he used the word “Hakenkruez,” which in German refers to the hooked cross that is so prolific in Christian iconography and with which Hitler was very familiar. According to T.K. Nakagaki, it was James Vincent Murphy, in his popular translation of Mein Kampf, who translated “Hakenkreuz” into “Swastika,” leading to a widespread misidentification, misunderstanding, and wrongful association of the swastika with Nazism and other destructive forces and actions. (See also Heller 2019 and Munson 2016).

Bibliography

Anti-defamation League. “Swastika.” Hate on Display. https://www.adl.org/resources/hate-symbol/swastika. Accessed 12 June 2018.

Aronis, Carolin. “The Technological Operation of the Swastika: A Media Ecology Approach.”ALCEU. (Rio de Janeiro, online), V. 22, Nº 46, p.96-117, jan./abr. 2022.

Aronis, Carolin and Eric Aoki. (2024). “Nooses and Nazi Swastikas on U.S. campuses: An Anti-racist Call for a Rhetorical Reframing of Hate Symbols as Violent Technologies.” Quarterly Journal of Speech. 1-28.

Campion, Mukti Jain. “How the world loved the swastika – until Hitler stole it.” BBC News. 23 October 2014. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-29644591. Accessed on 10 June 2018.

Heller, Steven. The Swastika: Symbol beyond Redemption? Allworth P, 2000.

—. The Swastika and Symbols of Hate: Extremist Iconography Today. Allworth P, 2019.

Munson, Todd. “The Past, Present, and Future of the Swastika in Japan.” Education about Asia. Winter 2016: Volume 21.3. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-past-present-and-future-of-the-swastika-in-japan/. Accessed on 24 July 2024.

Nakagaki T.K., The Buddhist Swastika and Hitler’s Cross: Rescuing a Symbol of Peace from the Forces of Hate. Stone Bridge Press, 2018.

Oxford English Dictionary. “Swastika, N., Sense 1.” Oxford UP, July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1181719309. Accessed on 5 July 2024.

Quinn, Malcom. The Swastika: Constructing the Symbol. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Simi, Pete and Robert Futrell. American Swastika: Inside the White Power Movement’s Hidden Spaces of Hate. 2nd ed., Rowman and Littlefield, 2015.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “The History of the Swastika.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/history-of-the-swastika. Accessed on 10 June 2018.

Wilson, Thomas. The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol, and its Migrations, with Observations on the Migration of Certain Industries in Prehistoric Times. 1896. Theophania Publishing, 2014.

Simplified Summary

The swastika is an ancient symbol that has been used by various cultures and communities in many different ways throughout history. It has circulated as a symbol of peace and goodwill, but it has also been used to spread hate and violence. While many people still perceive the swastika to be a benevolent sign, the swastika, in the United States, is most often recognized as a harmful sign due to its participation in hateful, antisemitic, and white supremacist actions. Some recent research suggests that it was the Hakenkruez (hooked cross) that was actually appropriated by Hitler and not the Hindu swaskita. Therefore, many argue that more education is needed to clarify this distinction. The Swastika Counter Project does not disagree. However, its research demonstrates that in the contemporary United States, the swastika does most often function and is most often perceived as a terrorizing tool (or technology) that participates in antisemitism, white supremacy, and white nationalist ideologies and behaviors. In addition, research findings demonstrate that higher education institutions and K-12 schools are frequently targeted in the United States. As such, the Swastika Counter Project especially advocates for teachers at all levels of education to help deepen students’ understanding of the contemporary and ongoing harms that swastikas perpetuate.